So I was recently in Costa Rica and stopped into a museum in the small town of Alajuela dedicated to Juan Santamaría, a national hero and a figurehead around which a part of Costa Rican national identity gathers. And as I learn more about Santamaría, I also, inevitably, came to learn about William Walker, a gentleman from the US who decided to independently annex (by military force and presumed superiority) much of Central America to be part of the slave-owning states of the South.

So I was recently in Costa Rica and stopped into a museum in the small town of Alajuela dedicated to Juan Santamaría, a national hero and a figurehead around which a part of Costa Rican national identity gathers. And as I learn more about Santamaría, I also, inevitably, came to learn about William Walker, a gentleman from the US who decided to independently annex (by military force and presumed superiority) much of Central America to be part of the slave-owning states of the South.

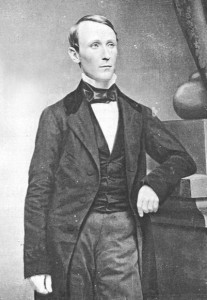

Walker, and others like him (because there always are others), were known as filibusteros in Spanish, filibusters in English, which means pirate or freebooter—men who weilded weapons under the guise or control of no nation, for their own personal gain (gives a whole new meaning to Congressional filibusters, doesn’t it?).

What struck me most is that a figure essential to the make up of Costa Rican national identity is virtually unknown in the US, at least he was completely unknown to me and the other Americans I’ve spoken to about him since. And I couldn’t help further wondering what such a figurehead must mean to the shaping of a Costa Rican understanding of US citizens. But then again, look at how so many Americans proudly proclaim themselves anglophiles after that little bit of history we call the Revolutionary War. Which really just got me thinking about a lot of other things. But rather than try to summarize those thoughts myself, I will borrow from a book by an American journalist that I picked up in a tiny used bookshop while on a brief stop in the beach town of Jaco about her year spent in Central Asia:

Imagining the lives of others is an essential human instinct. It is an act of empathy, a gesture of faith in a common bond. It is also a kind of travel, an attempt to move outside the parameters of our own narrow universe. But it almost always fails. Once we pick up and go—once we cross the borders, physical and intellectual, political and emotional, that divide countries and continents—we come to realize that we’re not merely imagining. We’re projecting. And if we’re honest with ourselves about that, we at least see the truths, or at least the puzzles and muddles in which they are buried.

—So Many Enemies, So Little Time, Elinor Burkett